Every writer I know looks forward to clutching the hallmark of her achievement. A rectangular paginated object is proof of years of a verbal mind at work, the book a harvest of a writer’s dedication.

Every writer I know looks forward to clutching the hallmark of her achievement. A rectangular paginated object is proof of years of a verbal mind at work, the book a harvest of a writer’s dedication.

We value concrete objects. We trust what we can hold and weigh in our hands, an object that stands the test of time. Tangible evidence, books secure us a place in culture and, by extension, the mind. Removing a book from the shelf and reading, an easy enough action, we open to a world that unfolds at our fingertips. The written word receives such respect that we devote entire buildings in the form of libraries to housing these esteemed documents of culture.

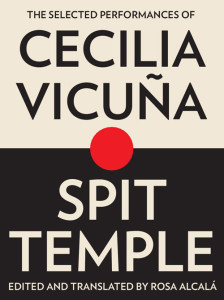

I revere the books that sit on my shelves, both the ones I sweated into production and the ones labored over by fellow writers. So, too, I imagine, does poet, filmmaker, installation and performance artist Cecilia Vicuna. Her book Spit Temple is a welcome collection of poems and transcripts of oral performances based in shamanic ritual, political oppression, and her Chilean indigenous roots, edited and translated by Rosa Alcala. Spit Temple reminds us about the power of the printed word as document, and equally valuable, the power of the spoken word.

Vicuna’s work elevates ephemeral voiced poetic actions into art. She privileges orality through whispers and songs, recurring vowels and syllables, and blends or slices of English, Spanish, and Andean Quechua that slides into new words. By presenting her work from the side of a gallery or outdoors, she presents herself as a vessel that conceives sound, motion, and meaning and as an instrument that transmits presence and change. By bringing attention to the formation of words and the chat between and during the reading of a poem, its start and finish unclear, she alters the definition of what’s possible in poetry. Her poetics values performance, the living body, a return to ancient practices as well as an embrace of contemporaneity.

In an excerpt from a 1998 performance in Buffalo NY where she unravels thread, which is a language and central metaphor in much of her work, she says,

the verses are very very very small

very short

but they contain

they contain

as many verbs

as many powers

as many rays

as many thunders

as

possibly

can be

included…. (p 161)

Through prose poems of conceptual performances, and letters repeated across a line or stanza, audience responses and her gestures bolded, her book maps several approaches to performance poetry as a union of space and text, the personal and communal, a body woven of multiple threads. “Writing is sensorial disorder,” she says in Dennis Tedlock’s essay, one of several in the collection.

Disorder, perhaps. Or a reordering that recognizes process as art.